By Reagan Carter, Lexi Friesel, Rordan Mullen, Connor Sturniolo and Allegra Vercesi

American journalists experiencing harassment believe social media amplifies the backlash they receive, and a December 2020 UNESCO report said it’s a factor forcing female reporters to leave the field.

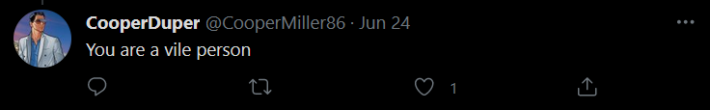

Susan Page, USA Today’s Washington bureau chief, has covered six White House administrations and 10 presidential campaigns, according to her USA Today biography. She has often been criticized by people across the political spectrum and is frequently denounced by Twitter trolls who disagree with facts.

Page, who moderated the vice presidential debate in October 2020, feels the creation of social media platforms means more harassment because there is now an easy and public way for people to spread hate. Page also noted that the journalists receiving the most hateful comments and feedback are political reporters, journalists of color and female writers.

“Online culture allows people on social media to spat off anonymously,” Page said in an interview Saturday.

Harassment of journalists is not a new issue, and it doesn’t seem to be going away any time soon.

Online harassment, as defined by Boston University, involves violent threats, damage of reputation, incitement of harm towards a victim as well as invasions of privacy. Journalists are often on the receiving end of these threatening messages, subjected to angry comments from users who feel strongly about the political stories reporters cover.

Measures taken to protect journalists have been ramped up in recent years due to the growth of hate on online platforms, and an increasingly politically divided world.

The Online News Association held a panel Wednesday about practices for supporting journalists who are subject to online harassment. The panel, moderated by Viktorya Vilk, program director for digital safety and free expression at PEN America, was targeted at journalists, newsroom leaders and heads of security.

The session description read, “In the face of rampant online abuse, our phones and laptops have become hostile environments, disproportionately impacting women, POC, and LGBTQIA+ reporters and undermining efforts to create more equitable and inclusive newsrooms.”

Twitter has put together multiple resources to assist journalists looking to connect with their audiences and deal with the tumultuous nature of hatred received. However, no official statements from social media sites such as Twitter regarding hate towards journalists on their platforms have been made.

Mizell Stewart III, a Gannett vice president, said in a telephone interview that the company, which is the parent of USA Today, follows a procedure depending on the harassment’s severity that may include getting company security involved.

Stewart said it is now Gannett company policy for journalists to separate personal and professional social media accounts. He emphasized the value of freedom of speech and expression, but stated that now with people taking advantage of that privilege online, harassment occurs.

“The main advice to any individual is to be mindful of how you use social media platforms,” Stewart said. “You should separate your personal and professional social media, but don’t let it dominate your life.”

Margaret Sullivan, a Washington Post columnist and author of the book Ghosting the News: Local Journalism and the Crisis of American Democracy, said some of her pieces have incited virtual hate.

“There have been times when I’ve had to report online harassment to The Post’s security staff and my editors,” Sullivan said in an email.

Trip Gabriel, who covers national news and reported on the 2012 and 2016 presidential campaigns for The New York Times, has had a different experience than Sullivan and Page.

“I’ve been fortunate not to have been harassed online as a journalist, almost certainly because I am male,” Gabriel said in an email.

A 2020 UNESCO report done in conjunction with the International Center for Journalism, revealed 73% of female journalists in its survey said they have been the subject of online violence as a result of their work. A quarter had received physically violent threats, and 18% had been threatened with sexual violence.

Four percent of the women surveyed left the field due to the threats and harassment. The threats even spill over into the real world.

UNESCO’s report confirmed that 20% of the female journalists who had received online threats also reported being attacked offline in connection with online violence they had experienced.

Sam Fulwood III, dean of the School of Communication at American University, shook his head in disagreement when asked if he believes there are solutions to preventing the persecution of journalists.

“There are no solutions,” Fulwood said. “Nowadays people don’t like journalists. You have to be comfortable with people not appreciating what you write.”

Nevertheless, people still report news, no matter what abuse they endure over time.

“Journalism is the best profession in the world,” said Fulwood, who worked as a metro columnist at The Cleveland Plain Dealer and as a national reporter with The Los Angeles Times.

He noted that although criticism as a journalist is imminent, the work is important nonetheless.

Fulwood said: “It’s not about you. It’s about the stories you tell.”